A Dancing Chameleon: iPad and the Emerging Shadow of the Cloud

April 23, 2010

Many technology pundits have asked what technological niche Apple's iPad is supposed to fill. The answer lies not in a tidy familial association to an existing device; instead, the iPad forces us to query the changing place of technology in our lives.

It seems like there are as many descriptions of Apple’s new iPad as there are publications. Business Insider called it “a big iPhone.” PC World, seeking a slightly more refined approach, called it “a big iPod Touch.” For its part, CNET called it a “touch screen tablet computer,” or what Intel defined as a “handheld touchscreen device often used to view multimedia and surf the web.”

Having used one now for nearly two weeks, I’d like to offer two thoughts on what the iPad is not. It is clearly neither a big iPhone nor a big iPod Touch, despite the fact that it can run applications for those two devices. It is also surely not a tablet computer, or at least any tablet computer that I have ever used. The performance of the Apple device contrasts readily with the ever niche-y tablet, which just never seemed to do anything well.

So if it’s not an iPhone or an iPod, what exactly is it? I’d like to place the product within Apple’s design and operations approach. That is, it is a device in an evolutionary ecosystem, a product that borrows from the past while illuminating the future. A kind of “knowledge navigator,” it announces its place in technological history by what it chooses to offer and by what it chooses to ignore about the technological environment around it.

It is a conventional device that offers an outstanding browsing experience, save for the well-documented lack of Flash support. It is an evolutionary device that takes the touch-and-click interface and expands both the vocabulary and reach of a new kind of GUI, one based on a “gestural user interface,” that succeeds the mouse and trackball the same way they succeeded the command line interface. It is a revolutionary device that combines the conventional and evolutionary into a package that is reasonably priced for most first world countries.

But if it’s so revolutionary, why the technological compromises that the techno cognoscenti decry about the device? Why no Flash support? Why no Video Camera? What about multitasking? The answers to these questions are all contained within a snapshot of our technological moment. About the only possible device ecosystem that can challenge Apple’s vision of defining the standards for the mobile revolution is Adobe’s Flash, which sits on millions of computers and hundreds of millions of mobile devices. It is neither in Apple’s short term or long-term interest to support this competing standard—in fact, Apple has everything to gain from undermining its dominance.

But if it’s so revolutionary, why the technological compromises that the techno cognoscenti decry about the device? Why no Flash support? Why no Video Camera? What about multitasking? The answers to these questions are all contained within a snapshot of our technological moment. About the only possible device ecosystem that can challenge Apple’s vision of defining the standards for the mobile revolution is Adobe’s Flash, which sits on millions of computers and hundreds of millions of mobile devices. It is neither in Apple’s short term or long-term interest to support this competing standard—in fact, Apple has everything to gain from undermining its dominance.

The questions about the video camera and the dreamed for iChat functionality is similarly entrenched in our technological moment. Everyone conceptually understands that the introduction of videoconferencing to the already congested wireless spectrum is inconceivable. Heard anyone speaking glowingly of his or her AT&T experience lately? Why introduce an emerging product with a capability that is sure to operate poorly and ensure a round of unfavorable reviews and ratings?

This, then, is the technologically inscribed iPad, announcing its dependency on infrastructure that hasn’t been built by AT&T while reflecting the strategic direction of corporate competition with Adobe. To my mind, I can’t think of any device I have ever used that so self-consciously plays with its own evolution while offering its function.

As surely as AT&T will build out its infrastructure with 4G, an iPad with iChat functionality will appear. But it will be, and this is critical in understanding the iPad, at the pace of offering this service to the general public and not just the “technologically elite” or the “early adopters.” The iPad is the device that Steve Jobs has been dreaming about as, “the device for the rest of us.”

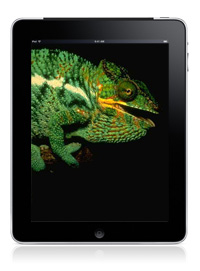

As much as it is the technological community that has attempted to define what the iPad is or isn’t, the reality is that the promise of the device is based on it resisting being pigeon-holed into some Best Buy product classification. Instead, it is not only a device for everyone, but also a device that can be what you want it to be, adapting to the form of your digital life. That’s why I call it a Chameleon device for living life online, able to adapt to its environment and to its user, becoming what its end-user wants it to be.

For if the iPad is anything, it is a device for navigating one’s digital life, which as I’ve suggested, is no longer the domain of just techies. It’s a walking photo album, holding five thousand of your personal pictures. It’s an eBook, allowing you to read John Grisham’s new novel while lounging in an armchair. It’s a financial tool, for closely monitoring stock and currency prices and any news flashes that bear on the market. It’s a video screen for in the airplane when you want your kids to watch Pixar’s “Toy Story.” It’s a real estate portfolio manager, providing geo-located house sales, with accompanying tax and comparable sales. It’s built-in medical text with automatic quiz modules and it’s a newspaper reader, for looking at not only all the text that is fit to print, but also the video and audio that might complement it

For if the iPad is anything, it is a device for navigating one’s digital life, which as I’ve suggested, is no longer the domain of just techies. It’s a walking photo album, holding five thousand of your personal pictures. It’s an eBook, allowing you to read John Grisham’s new novel while lounging in an armchair. It’s a financial tool, for closely monitoring stock and currency prices and any news flashes that bear on the market. It’s a video screen for in the airplane when you want your kids to watch Pixar’s “Toy Story.” It’s a real estate portfolio manager, providing geo-located house sales, with accompanying tax and comparable sales. It’s built-in medical text with automatic quiz modules and it’s a newspaper reader, for looking at not only all the text that is fit to print, but also the video and audio that might complement it

The iPad thrives with anyone who has a daily digital life and might be the first commodity device designed for life within the cloud. Oh, and did I mention that it has an excellent email reader, maybe the best I’ve ever used as well as a fantastic date book. This from a generation one device.

The iPad will change and it will adapt because it is a (r)evolutiontary product growing out of Apple’s iTunes ecosystem and into the technological capabilities of wireless infrastructure and cloud services that mark our future. It is ultimately a product that speaks not to a new type of device, but rather to a new role of technology in our life. Not for nerds, but for everyone, who increasingly find themselves touched by the cloud. And as the iPad evolves, we evolve with it, taking an activity like reading and adapting it to our digital age-whether it’s texts, newspapers, books, essays, movies, podcasts, interviews, videos, financial statements, or code—it’s at home with them all.

The question finally is, are we at home with it? Which ultimately isn’t the story of a $499 device but rather the tale of how we feel about the way our digital lives continue to evolve and how comfortable we are with the emerging shadow of the cloud.

- Alan Cattier, Director Academic Technologies